Happy Martin Luther King Jr. Day from RILN; today reminds us of the progress we have made and the progress that lies ahead in intersectional racial equity in areas such as the U.S. adult and juvenile justice systems.

Historic civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested 29 times in his lifetime. His time spent in prison shed light on the racial disparities within the criminal justice system – disparities that persist 60 years later.

“Law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and that when they fail in this purpose they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress,” he wrote in 1963, Letter from Birmingham Jail.

While there’s been in-depth research and discussions on the unequal representation of Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous people in the U.S. adult criminal justice system, advocates are calling attention to the power behind juvenile justice entities.

“Without that recognition that children and youth have unique needs or will understand and respond differently than adults, we miss a huge opportunity to rehabilitate and promote the future well-being of our youth and communities,” RI Kids Count wrote in Centering Youth Voice in Juvenile Justice Reform.

In the United States, about 1,995 youth are arrested every day, according to The State of America’s Children 2020 report.

These youth may be placed on probation or removed from their homes and sent to correctional institutions or other residential facilities. Experts have pointed out major issues with juvenile facilities including exposing youth to further violence and maltreatment, a pervasive overreliance on confinement, along with glaring racial and ethnic disparities.

“Youth commit only a small portion of the nation’s crime…[and] has also been going down for many years,” according to the Campaign for Youth Justice. “Despite this drop, the United States has the highest rate of youth confinement of any developed country. In 2010, there were 173 youth for every 100,000 in confinement. However, 39% of those who are in confinement are there due to a technical violation of probation, drug offenses, public order offenses, status offenses, and low level property offenses.”

Various reports have all found that youth of color and those with disabilities, along with LGBTQ+ youth are highly overrepresented in the juvenile justice system.

As of 2021, “Black youth are nine times more likely than white youth to receive an adult prison sentence, American Indian/Alaska Native youth are almost two times more likely, and Hispanic youth are 40 percent more likely,” according to the Children’s Defense Fund.

Research experts estimate between 30 percent to 85 percent of incarcerated youth have a learning disability, making students with disabilities almost three times more likely to be arrested than their peers.

LGBTQ+ youth make up five to seven percent of the youth population, but 13 to 15 percent of the juvenile justice population, according to the Center for American Progress.

RI KIDS COUNT REPORT: Key Findings & Recomendations

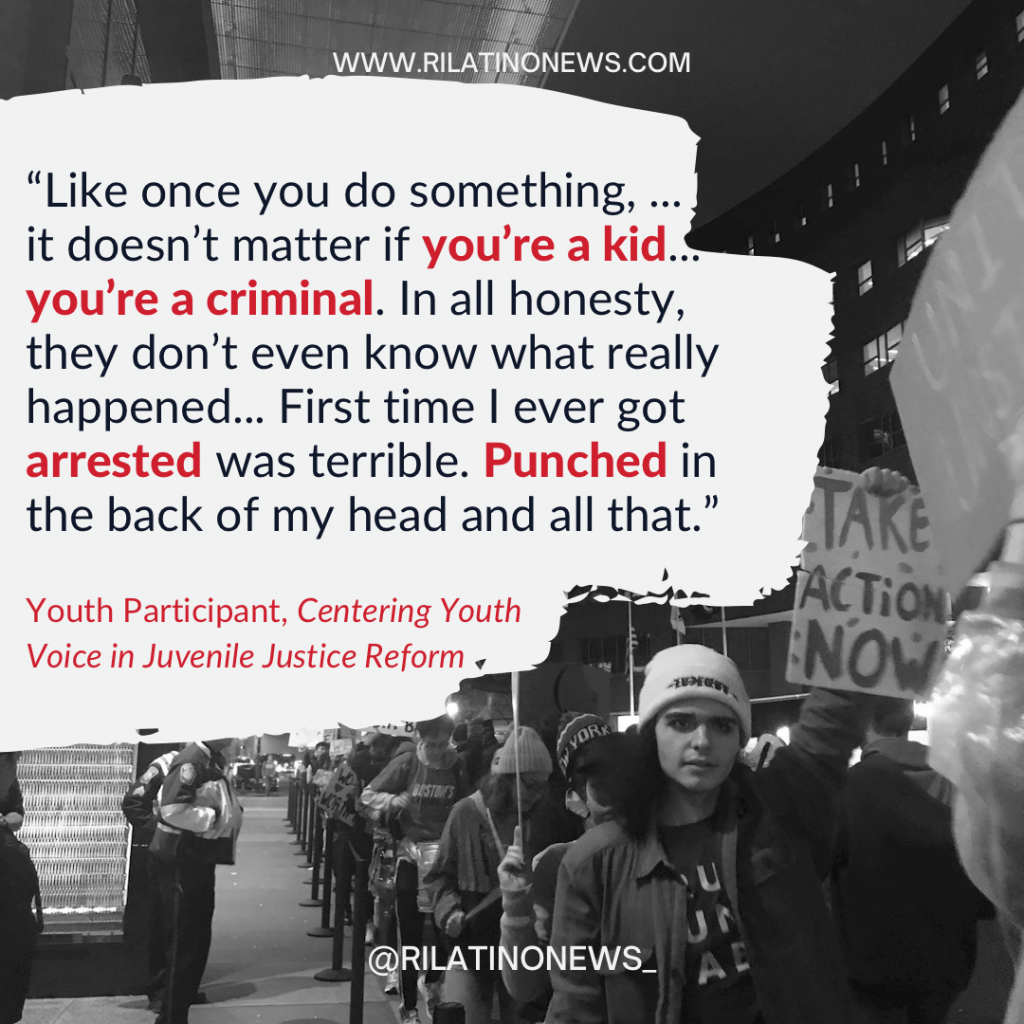

Last month, RI Kids Count published Centering Youth Voice in Juvenile Justice Reform. The report highlights the experiences and perspectives of Rhode Island youth (14 to 21 years old) who have come into contact with the juvenile justice system.

An event to explore and discuss the report’s findings was hosted on Dec. 11 and is available to watch HERE.

Major takeaways included the need to address “the trauma many youth have experienced and continue to experience… unequal access to legal representation and the ability to pay fees…[and] racial and ethnic disparities at all points in the juvenile justice system.”

Youth participating in the focus groups said they felt intimidated by the entire family court process and did not have a voice in their own case.

“I think each judge needs to understand that they are talking to a kid…this kid doesn’t know you, so they are uncomfortable,” said one youth participant. “They don’t know you and then they’re being watched by other people too. So, it puts you in a place where you don’t really feel like answering.”

A community-based alternative to family court are Juvenile Hearing Boards, a process that promotes restorative justice.

“The open dialogue afforded by restorative justice opportunities gets at the root cause of a youth’s actions by centering their voice in the narrative,” according to the 2022 report.

All nine focus group participants identified as youth of color. The groups spoke on experiencing racism in encounters with policing, courts, detention, and probation.

“We should all be equal and the consequences should all be equal. It shouldn’t be based on your skin or how the judge is feeling that day,” said one participant.

The publication’s recommendations include that more people of color are recruited in all areas of the system and objective screening tools such as the Risk Assessment Instrument are considered at arrest.

Overall, participants who have been to the Rhode Island Training School said the experience was counterproductive and harmful to their wellbeing—especially to their mental health.

“When I went in there, I wasn’t even 18… but it did change me,” said one youth participant. “That’s why I changed, because I was by myself a lot like I couldn’t be around nobody no more…I was just… in my room, depressed, by myself, just like, damn. Then I started being anti-social…”

Child advocates worry that such programs restrict youth’s development instead of providing effective rehabilitation.

“…treating kids like little adults obviously always does nothing but tarnish them and hurt them and not give them [a] chance to change while their brains are still developing, and their emotional responses are still growing,” one caseworker told RI Kids Count.

On crime prevention, participants called for more accessible after-school activities, career entry opportunities, and adult role models from their communities who can relate to them.

“…The reason why kids are getting into trouble right now, because they don’t have…well everything runs on money… you have to pay for the YMCA, Boys & Girls Club…we don’t have money…we don’t have a job…all we can do is get into trouble,” said one youth participant.

Learn more about the publication’s findings and recommendations for juvenile justice reform at rikidscount.org.