BRISTOL—Hispanic household owners are the most cost-burdened in Rhode Island, which is defined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development as households that pay more than 30% of their income towards their house.

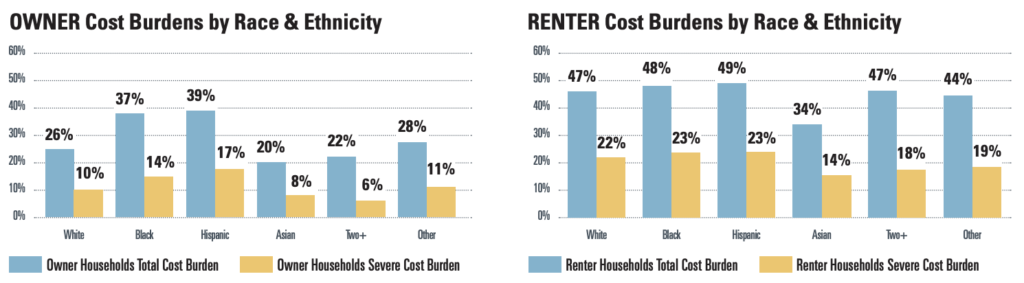

According to the Housing Works RI 2023 Housing Factbook, 72% of Hispanic renters are cost-burdened, with 23% of them paying more than half of their income in housing costs, and 56% of Hispanic household owners are cost-burdened with 17% paying more than half of their income in housing costs. Paying more than 50% of your household annual income in housing costs effectively makes people house insecure, and statistics show that Rhode Island’s Hispanic population experiences housing insecurity at a higher rate than any other racial or ethnic group.

“If demand is high and supply is limited, prices go up, and that’s exactly what has happened in this market, and unfortunately, it’s way too high for the average worker in the state,” explained Brenda Clement, Director of HousingWorks RI at Roger Williams University.

More than 150 thousand households in the state are cost-burdened, according to the Rhode Island Foundation. That’s 30.86% of Rhode Island’s approximately 486 thousand housing units for a little more than 1 million residents. Rhode Island also has the lowest number of building permits issued each year.

The city of Providence is now the 20th most expensive city to rent a one-bedroom apartment, according to a recent Zumper report. A Zillow report found that Providence rent has increased 6.9% from June 2022 to June 2023, which is tied as the second highest increase with Hartford, Conn., and just below Boston, Mass., at 7%.

“Cities like Providence, Central Falls, Pawtucket, and even Cranston have a huge Latino population,” said Executive Director Marcela Betancur of the Latino Policy Institute, explaining that the lack of affordable housing in those cities is particularly affecting the Latino population.

According to statista.com, the average family median income for Hispanic households is $62,800. The Rhode Island Foundation calculates that a family’s median income to buy a home in the state needs to be $94,183. Betancur suggested that raising the minimum wage may help if the state can ensure it meets the actual economic needs of the population.

“By the time we get to $15 an hour in two years, we’re going to probably need $20 an hour to live a basic life,” Betancur added.

According to the Rhode Island Foundation, the state ranks at the bottom half in most categories that involve addressing housing issues. To start, Rhode Island isn’t building enough housing for residents in need. In 2021, Rhode Island’s issued housing production per 1,000 residents ranked last in the nation at 1.27. Rhode Island has ranked 38th in annual housing production per 1,000 residents over the past decade. This low supply of housing has also been met with high demand, causing prices to soar.

According to Dr. June Speakman, who serves for the 68th district of Rhode Island House of Representatives and is a political science professor at Roger Williams University, 27,000 units of housing need to be built to diffuse the situation in the urban core part of Rhode Island, in locations such as Providence, Pawtucket, and Central Falls. These are the areas where most people want to live because there is an abundance of job opportunities. Speakman said it would not make sense to build a 300-unit apartment in a place where there are no job opportunities for new residents.

Another way to address the issue is to change the zoning rules, said Richard Godfrey, who is the executive director of the Cummings Institute for Real Estate at Roger Williams University and was the executive director of Rhode Island Housing for 21 years.

“We need to change the zoning to allow more sensible development, better uses of our commercial districts, and allowing more homes per acre. Four homes per acre is low density,” Godfrey said.

The physical infrastructure—such as building water supply and sewage, for example—is only one aspect of the problem, according to Speakman.

“Half of the people who are unhoused probably could easily move right into an apartment and feel happy if someone paid their rent; others are more difficult, and they need what we call permanent supportive housing,” she said.

For example, people suffering from mental health illnesses might need further support aside from housing opportunities to prevent them from experiencing homelessness, such as high-quality healthcare and access to medication and providers, Speakman explained.

“It really depends on why the person is houseless,” she said.

Private developers are responsible for a majority of the construction, and they have no incentives to reduce the selling or renting prices, according to nonprofit organizers. Usually, funding from government and nonprofit organizations are required for developers to build affordable housing. The state is putting money towards efforts to create housing, but Rhode Island lags behind other states in the country in tackling its housing crisis.

SUGGESTION: State Presents Shelter-Focused Plan Amid Calls For Long-Term Solutions

Looking At Out-Of-State Efforts

In Seattle, Wash., Homestead Community Land Trust and Habitat for Humanity Seattle-King County—two non-profits that specialize in helping lower-income residents become homeowners—operate a community land trust model. Their homes are available to lower-income residents making less than 80% of the area median income, which was $95,300 for a family of four in the Seattle area when this story was published.

These community land trusts work by gathering money from the city, county, and state, along with philanthropy and private donations. These funds are then managed to support land acquisitions, housing development, and ongoing operations.

The city of Seattle offers funding to nonprofits like Homestead and Habitat for their affordable homeownership work, down-payment assistance for low-income homebuyers to buy on the open market, emergency foreclosure assistance, home repair, and weatherization. This helps people in Seattle who are falling behind on their mortgage payments, homeowners who are low-income residents, and families who need to purchase a home with financial assistance. Land trust owners can continue to live in their homes if they can keep up with their mortgage payments.

In-State Efforts To Address The Housing Crisis

Non-profit housing and homeless advocacy organizations in Rhode Island are working hard to find safe and reliable housing for residents in need. Amos Housing, based in Providence, is a recovery-based organization that helps low-income residents find housing. It works with other organizations across the state, such as Crossroads, House of Hope, and the Rhode Island Coalition to End Homelessness.

Jessica Salter, Chief Philanthropy and Communications Officer at Amos Housing shared that the most pressing issue in Rhode Island is its lack of available, affordable housing units.

“This is a problem that Rhode Island has spent decades creating, so it’s not going to be fixed in a year or two. You’re talking about government funds, you’ve got to put it up for bid, you’ve got to find a developer, you’ve got to find out where it’s going to be built, then you’ve got to do the building. So, it’s a three to five-year process.”

Jessica Salter, Amos Housing

Crossroads Rhode Island is one of the biggest non-profit organizations in the state. Due to an increase in rent, Crossroads is seeing more families and individuals experiencing homelessness.

The organization uses a housing first model that was inspired by Iain De Jong, which it has been practicing for the past nine years. The housing first approach involves promptly providing permanent housing to unhoused individuals or families without requiring them to resolve the underlying issues that caused their homelessness before accessing housing. Additional supportive services are offered after they are securely housed.

“Research has shown that it’s more effective to house a homeless person and then provide them with wraparound service,” explained Teresa Luzzatto, director of adult shelter services at Crossroads.

Crossroads is starting the groundwork to help residents find homes. They have recently kicked off a construction project that will build 176 apartments on Summer Street in Providence for formerly unhoused residents. “The only answer to ending homelessness is affordable housing,” Luzzatto said.

It will take time before the organization can start housing individuals, but on the brightside, Luzzatto feels that Rhode Islanders are aware of the crisis and are trying to put their best foot forward.

SUGGESTION: RI Opinion+: Juan Espinoza and Melissa Cruz

There are over 25,000 Rhode Islanders who are currently on the waitlist to receive Section 8 housing vouchers. The state is offering landlords an incentive to encourage homeowners to lease their apartments to residents who have a Section 8 voucher.

According to Luzzatto, a long-term goal of Crossroads is to have all their clients signed up for a Section 8 subsidized waitlist and get them into homes. Rhode Island’s average wait time to receive a Section 8 voucher is 24 months.

Rhode Island’s neighboring state, Massachusetts, is also having trouble with its Section 8 vouchers because many people have been on the waitlist for so long, even though there are a number of vacancies. In 2014, Massachusetts created a statewide online system called the Common Housing Application for Massachusetts to make it easier to apply for housing, but it ran into problems in late 2018 and has cost the state $6.8 million dollars. Massachusetts still has problems with affordable housing, and the complaints have only grown louder. ·

While solutions for the housing crisis may take time to ameliorate the issue, Uprise Rhode Island has created an artificial intelligence chatbot that answers residents’ questions regarding renters’ rights, housing assistance, and consumer complaints. Communities of Hope Civic Media reporters tested the app and found it very useful, finding that it will also answer questions on related topics such as food assistance. As long as the chatbot is given enough details, it serves as a useful tool that connects individuals with helpful resources.

If you’ve just become homeless and are trying to figure out what to do next, the chatbot will help connect you to relevant organizations, providing their phone numbers and nearest locations for immediate assistance. Although this is a new tool that can provide useful information, the questions to the chatbot need to be very specific and are only limited to five entries per day as it’s still a new service.

If you are experiencing homelessness or at risk of experiencing homelessness, you can contact the Coordinated Entry System run by the Rhode Island Coalition to End Homelessness for assistance at 401-277-4316 or online at www.cesri.info/.

More Resources Mentioned In This Story

- Amos Housing Emergency Assistance: https://amoshouse.com/what-we-do/emergency-assistance

- Crossroads Rhode Island Emergency Shelters: https://www.crossroadsri.org/housing-services/programs-services/emergency-shelter

- UpRise RI The Helping Hand Chatbot: https://upriseri.com/hh/

- RI Coalition To End Homelessness Resources Page: https://www.rihomeless.org/help

This report was published in collaboration with the Communities of Hope Civic Media at Roger Williams University to shed light on how the state’s housing crisis disproportionately impacts Hispanic/Latino communities and on the range of ongoing local efforts to address this urgent issue. Jeannette White, Jack Aviles, Tessa Uden, and Mat Clarke contributed to this story.

Stathi Savvidis is a senior studying Journalism at Roger Williams University. He is of Greek descent from Brooklyn, Connecticut. Writing about current topics affecting communities drives his interest in writing. Besides writing, he likes to go running and watch sports games. He is looking forward to covering more stories and building up his resume in the future.